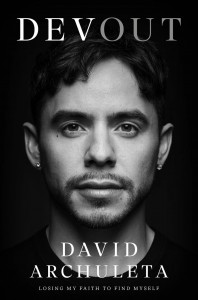

In his new bombshell autobiography, Devout: Losing My Faith to Find Myself, pop singer David Archuleta writes with heartbreaking candor — admitting that at times he even wept while typing — about his life-long battles with poor self-esteem, extreme people-pleasing, scrupulosity (a subtype of OCD characterized by religious obsession), guilt and denial regarding his closeted queerness, and eventually suicidal ideation, before he finally came out at age 30 and then left the Mormon church.

But he says the two topics that were the most difficult for him to write about were actually his ”terrifying” run on American Idol (memories of which he’d almost entirely blocked out) and his fraught relationship with his notorious father and “dadager,” Jeff Archuleta.

“I had not yet processed my time on American Idol, which I think I associate a lot with my relationship with my dad,” he explains softly.

Back in 2008, when David was a frontrunner on Idol and the show still dominated pop culture, Jeff practically made TMZ and VoteForTheWorst.com headlines more often than David did — all about being him an overbearing “stage dad” who quickly created enemies on the Idol set (and was even ultimately banned from the set). And Devout reveals that such gossip was actually true. A man with deferred dreams of his own greatness, Jeff forced his talented but extremely shy child into the spotlight — dragging David from Utah to Los Angeles (where they often slept in parked cars instead of hotel rooms) to audition for Star Search and loiter in hotel lobbies hoping to network with American Idol Season 1 contestants and executives.

Back in 2008, when David was a frontrunner on Idol and the show still dominated pop culture, Jeff practically made TMZ and VoteForTheWorst.com headlines more often than David did — all about being him an overbearing “stage dad” who quickly created enemies on the Idol set (and was even ultimately banned from the set). And Devout reveals that such gossip was actually true. A man with deferred dreams of his own greatness, Jeff forced his talented but extremely shy child into the spotlight — dragging David from Utah to Los Angeles (where they often slept in parked cars instead of hotel rooms) to audition for Star Search and loiter in hotel lobbies hoping to network with American Idol Season 1 contestants and executives.

Such aggressive tactics actually worked, and David ended up competing on Idol Season 7, when he was just 16, making it all the way to second place. But David resented his controlling father’s pushiness and manipulation (as did the rest of the Archuleta family; Jeff’s laser-focus on his son’s singing career alienated not only David’s four siblings, but David’s own adored mother, Lupe). It was understandably stressful for someone so young and introverted to perform for votes on national TV while fearing he’d be “exposed” for being different and effeminate; to feel responsible for fulfilling his dad’s ambitions; to feel pressured to be a Mormon posterboy; and to eventually become the family’s breadwinner, after he signed a deal with Jive Records and continued to be managed by Jeff. It was only many years later, when a Mormon church elder warned David that he was being emotionally abused by his father and advised that David go no-contact, that David realized how extreme the situation truly was.

However, it was when writing Devout (which he was inspired to do by his good friend, former child star and I’m Glad My Mom Died memoirist Jeanette McCurdy) that David finally unpacked the secret that lay at the heart of his familial dysfunction. “[Jeff] was wrongly accused of things in my family that I didn’t really get a clear picture on until I was older, putting everything together and realizing, ‘This is a messy situation. This is complex,’” he says.

When David was 9 years old, a vindictive family friend on Lupe’s side falsely accused Jeff of sexually molesting David’s sisters, which had tragic, lasting ramifications for the entire family — especially for David, who came to fear and mistrust his father for years, long after Jeff was exonerated. And while David may never forgive the people who spread these vicious lies (as he discusses this family scandal during his Lyndsanity interview, his anger is evident), by writing Devout, he came to understand Jeff’s trauma… and forgive his father.

In the emotional video interview above and text Q&A below, David also opens up about watching his American Idol episodes for the first time in years and feeling newfound compassion for his younger self; how his fellow Season 7 contestant, the openly queer Adore Delano, made him “so seen and safe” during his Idol experience; and how he finally started living for himself at the late-blooming age of 30.

LYNDSANITY: We’ve done a lot of interviews in the five years since you came out and reinvented yourself professionally and personally. But as I found out from reading this book, you’d lived nine lives before that happened. You lived several lives even before American Idol. But it seems like you really started living at age 30.

DAVID ARCHULETA: It very much was like starting life again. In ways I was a late bloomer, but in other ways a lot of life had already been lived. There’s a lot of challenges. There’s a lot of public knowledge of parts of my life, while other parts I felt like I had to do everything to hide. Not just my family dynamics, but hiding from myself, with trying to figure out whether I was gay or not, and landing on bisexual — I just say “queer” now, to be broader, but it’s basically bisexual — and just feeling like I always had to live my life for someone else, for someone else’s approval. “Are you giving me the OK? Did I do this right?” I guess it was performative. Always performing. And I guess I never turned the performative part off until I reached my thirties. It was kind of like learning how to just finally exhale, after holding your breath for so long, and just saying, “OK, what’s it like to just be myself, regardless of what others may think of that?”

And it’s terrifying. It’s scary, because up until then, my whole identity was, “Do you like me? Do you approve of who I am? I will do whatever I need, I will be whoever you need me to be, in order to be accepted by you and approved by you and to be told, ‘Good job.’” To turn that off was terrifying, because I didn’t know how to live my life in another way.That’s why it was like restarting, because it’s like, “Oh, I’m going to live my life based off of what feels right to me.” Something I never believed I could trust, really. But yeah, it’s been so fun and exciting to just live. I feel so excited about life. Before, I was always so afraid of life.

Yes, a recurring theme in this book is you were a people-pleaser, whether you were trying to gain the approval of the Mormon church, American Idol voters, or especially your dad. As I said, I’ve interviewed you several times in recent years, mostly about either your sexuality or your changing relationship with religion, which are of course big focuses of Devout. But today, I want to talk about what you say were your two hardest things to write about: your father and American Idol. I’ll start by asking, why was that the case?

It’s probably because I already processed my sexuality, but I hadn’t yet processed the dynamic with my dad. And I had not yet processed my time on American Idol, which I think I associate a lot with my relationship with my dad. The way I coped to move forward with my life was simply to cut out a lot of that. Originally I didn’t [write] as much about American Idol [in Devout]; I talked more about my family dynamics and my religion, my growing up in Utah. And the publishers were like, “Hey, we would really love for you to talk more about your time on American Idol.” And it was just very uncomfortable.

I’m not saying it was a horrible experience. It was just extremely uncomfortable to go through. So, I went back and rewatched all of my American Idol episodes, and I experienced the cringe — but mixed with the cringe, this time I was feeling something new, which was compassion for the teenager that was there on that stage feeling so exposed, so uncomfortable, and really terrified. I mean, I was terrified to be on there, because I was so afraid of people seeing me for the “problem” that I was, that I thought I was. I mean, at the time, it was the problem that I was.

Do you mean people thinking you were a sissy? I’ll use the term “sissy” instead of a meaner one, but do you mean outing you, or figuring out what you maybe hadn’t even figured out about yourself yet?

Yeah, exactly. I think people labeling and deciding what I was, before I even understood what it was. It felt, again, like a loss of control — that I didn’t have control over the pacing of my life. I think that’s what was hard about American Idol. I was being forced to move at a much quicker pace than I was ready for. But I still did it because I didn’t want to disappoint anyone and I didn’t want to let people down, especially my dad. It was everything for him that I was there. He felt like I was finally experiencing what he always knew about me. He’s like, “David, you are one of the best singers in the world!” I was like, “Oh my God, Dad. There are plenty of singers out there. There’s Celine Dion, there’s Whitney Houston, there’s Mariah Carey, there’s Stevie Wonder. I’m not one of the greatest singers in the world!” But doing so well on that show for my dad was just like, “See what I told you? Didn’t I tell you?”

The irony is, even though Jeff was such a taskmaker that he made you almost hate music at times, like he sucked the joy out of it for you, you still do music for a living now. And you seem to enjoy it more than ever. And your whole music career might not have happened if Jeff hadn’t been such an aggressive stage dad. So, yeah, in some ways he was “right” to do what he did. How do you come to terms with all that? You must feel quite torn.

You are so right. And that’s a great observation that you’ve made. There’s a lot of resentment that I had had for my dad, but I couldn’t help but acknowledge that if it weren’t for his hardheadedness and his stubbornness and intensity… I’m a much more gentle personality. I’m a lot more passive. I’m still intense and passionate, but as far as my convictions, they just were not anywhere near the same level as where my dad’s were. He believed that I deserved to have success, and he believed that he deserved to see success from his son.

I didn’t have that same fire. I didn’t have that same drive. I wasn’t as motivated. I was just kind of fine to go with the flow. That’s just how I had always been. I did love music, but I was very shy. I was shy to sing in front of people, and my dad always pushed me to sing for people. I hated him for it, I resented it, and yet it taught me to go out of my comfort zone and take risks and do things that I didn’t always feel like doing because I didn’t feel like I was capable of doing it. It’s not necessarily that I didn’t want to sing. I just didn’t think I was good enough. I didn’t think I had the personality. I didn’t think I had the talent, abilities. I just questioned myself and second-guessed myself way too much to really do anything about it, whereas my dad was like, “No, we are doing this!” …That’s exactly what my dad was for me. To make it, especially in the entertainment industry, you need that.

Well, he got the ball rolling and put you on a path you might not have been on otherwise, but even after Idol, him being your manager created problems. Are there ways that he might’ve sabotaged you professionally — maybe that you didn’t even realize until later — where you feel like your career might’ve turned out differently if he hadn’t been in the picture?

Absolutely. I feel like while he helped start the first momentum for my career, he had very much an us-against-the-world mentality. It’s “us-against-them,” which I think stems from how we were raised with our beliefs … always being taught that the entertainment industry was “evil.” I think he was just kind of waiting to see all the “evil” people, so he treated everyone as if they were evil. “These are bad people who want something. They probably want to take advantage of my son.” And there are probably a lot of people who did. But I think at the same time, my dad didn’t realize that he, of all people, was the one who was taking the most advantage of me.

And I think because he was my dad, he thought, “Well, this is my son. I know what’s best for him, and I only want the best for him.” It’s like his vision was blurred by that sentiment, to not realize that a lot of my grief was coming from my dynamic with him and the way he was treating me, and how he didn’t recognize his own greed in some of those moments. And I don’t think he’s even in a place to recognize all of that, because in his eyes, he was just a dad trying to protect his son.

I assume he’s read your book by now.

No, he hasn’t. I’ll send one to him today. I’m actually sending all my copies out today.

Wow. I mean, Devout isn’t completely bashing Jeff, but you really go there. I actually surprised how much you went there. I thought you’d focus more on either your American Idol era or your post-coming out era, but I’d say the core of Devout is about your unhealthy family dynamic, namely with your father. I’m shocked that he hasn’t read it yet. How do you think he’s going to react?

I wanted to finish my story and publish it without any exterior influence on what my story is. I’ve been told many times what my story is and isn’t by others, and I did not want anyone distracting me from that. I knew my dad would have heavy opinions about it, because his perspective is different from mine. I’ve heard his perspective many times; it’s time for me to share mine. I’ve tried to share my perspective with him before, and he would get too defensive. He would feel like I was attacking him, so he wouldn’t hear me. He would speak over me. He felt a need to protect himself from the accusations he felt I was making against him. And my dad, he has trauma with accusations. He was wrongly accused of things in my family that I didn’t really get a clear picture on until I was older, putting everything together and realizing, “This is a messy situation. This is complex.’”

Just to make it very clear, your dad was falsely accused of child molestation, but it broke my heart to read that you always wondered back in the back of your mind, “Is my dad a bad guy? Is there any truth to this?” Has Jeff been given any heads up about how deep you go into all this in your book?

Well, part of the legal aspect of writing this book is like, “Hey, you say a lot of heavy things about your dad, and this could be really serious.” So, my collaborator Val [Valerie Frankel] joined me on a call and recorded a conversation I had with my dad and one of my sisters. I was really worried because I thought, “My dad does not want to talk about this. He’s moved on from this.” This is like 20 years ago that this happened. It’s not always the healthiest thing to go back and dig up the past. But I felt like this was necessary in order to find relief for my sisters, especially my older sister. She wasn’t the one on the call, but she was the one who was wrongly labeled as a victim of my dad, when it was actually someone else [in the family] who she was a victim of. And when she spoke up for herself, which I was so proud of her for doing, when she was young, she was silenced, because people were like, “Oh, you didn’t say what we wanted you to say.” And then for my other sister to have been bribed with a doll, trying to get her to talk poorly about my dad… she didn’t understand why.

When I was writing the book, I had to retract a lot of things because it was too much, and just for legal purposes. But I encountered some of the people in that circle of my family, like family and friends that were close to my mom and her side that kind of instigated all this, and I was just like, “I just am trying to understand. You were all so set on what my dad did. Can you give me some clarity? When did this happen? What did you see that made you convince 9-year-old me that I had to be on your side to get my dad into prison? Because that’s really affected me psychologically.” And it did affect me psychologically. I think the biggest thing that people saw on my time on American Idol was me being afraid of my dad — that narrative. And I was still processing it as a 9-year-old, because I didn’t get to really fully process it.

I didn’t understand what was bad about my dad. I just knew that touch was bad. So, if my dad touched me, if he would just put his hand on my shoulder, I thought that was bad. And that’s really the most he ever did to me physically. If he was standing by me, I just thought, “Don’t touch me.” It really messed with me psychologically. Now I’m finally in my thirties confronting these people, and I was just like, “What did you see that caused you to be so concerned?” And they said, “Oh, we actually didn’t see anything.” I was so pissed off. Fucking pissed. I was like, “You realize you destroyed our family, because you convinced us that we needed to look at our dad as if he were a monster!” And it was like, “Well, your dad was this way and he’s rude and he was insulting.” And I was like, “That does not justify accusing him of child molestation. He can be an asshole. He’s a jerk. He says crass things. He doesn’t respect people’s feelings. He says a lot of very rude things. We can acknowledge that that is a problem and that he can be manipulative and he can be controlling. But that does not justify accusing him of being a child molester.” It doesn’t.

Of course.

And when I saw the way that accountability was deflected, I was so mad. I was like, “You guys let us believe that for decades!”

I’m mad for you and for your family, just hearing about this!

And their answer was, “Well, God knows our hearts, and God’s the judge.” And I’m like, “I don’t think this is God knowing your heart was in the right place, because what you did was wrong, and you’re not willing to own up to that what you did was horrible.”

Have the people who started this chain of false accusations read the book? Do they know that you’re …

Everyone I talk about knows I talk about them. And a lot of them aren’t happy about it. But when I told my dad, I was like, “Dad, I need to get some information about this. I don’t know if this is too touchy of a subject, but I talk about the accusations that were made about you by some of the circle of our family and family friends.” My dad said, “I would actually love to talk about this. I felt like no one ever asked about my experience with that.” And we didn’t [talk about it back then], because the attitude was just, “Let’s just move on, let’s forgive and forget.” And so, my dad was relieved to talk about it now.

I interviewed my mom as well. My mom was just like, “David, why do you feel like you have to talk about this?” It was a very traumatizing experience for her. She didn’t know who to believe. There were two sides of people she loved and trusted, and they were contradicting each other. And she’s like, “Do I side with my circle of my people that I grew up with, or do I side with my husband?” It was very difficult for her to know what to do, and it broke her. She just shut down, and she didn’t recover from that for years. The marriage wasn’t the same after that. My mom basically was just checked-out. She stopped. She was in bed so much of the time. Her depression was really heavy.

And after that, my dad had a lot of frustration. It wasn’t until then that my relationship with my dad became complicated. Before that, he was just my dad. I loved him. We got along really well. There wasn’t this weird dynamic between me and my singing. It just felt like normal. I think my dad became more obsessed with my career and my singing when he needed an escape and an outlet from watching that his family was falling apart and knowing it was probably never going to recover. That’s when he started taking me to California and chasing this dream.

But at that point, my mom was like me: She was confused and she didn’t know what to believe. And no one ever listened to my sisters. So, it wasn’t until my thirties that my mom finally got clarity too about what happened. When I was first writing the book and talking to my mom about it, she’s like, “Well, I guess we’ll never know.” I was like, “Mom, you’ve heard [David’s older sister] Claudia. You’ve heard [David’s younger sister] Jazzy. You should talk to them again, hear their story.” And she did. It was really hard for my mom to revisit because she was just like, “If I learned the truth, it means that my family and my family friends were lying to me.” I think my mom never wanted to have to come to terms to that. But she finally was just like, “I realize I need to be there for my children. And if it means making it a messier dynamic with the people I always grew up with and loved, so be it.”

It was hard. But this all happened while I was writing the book. … When I first started writing, I didn’t know. I was like, “I still don’t know if my dad molested my sisters or not.” And I talked to my sisters and I was like, “Well, Claudia’s always said that Dad never did anything to her, but maybe she was hypnotized or something.” But if [my family] really cared about my sister being a victim, they would care about who she did remember touching her and the multiple accounts that she does remember of [her actual molester]. … Oh my God, I was just so pissed off. So pissed off.

I can hear and see your anger, and I don’t blame you. But you did finally get some answers. You got closure. And I know you were or no- or low-contact with your father for some time, and maybe you still aren’t the best of friends, but I was very pleasantly surprised to read about your dad’s reaction when you came out five years ago. I would’ve expected him to be livid, or say you’re ruining your career, but he was actually super-supportive. That was the absolute opposite of what I would’ve expected from him, and maybe of what you would’ve expected. That’s pretty huge.

Right. At that point, I had not been talking to my dad for a few years. And I think those boundaries were what we needed. We needed to have space to grow away from the toxic codependency that we had in our relationship. Having that space allowed him to become his own person. It allowed me to become my own person. … And just for my dad to only have positive things to say — to say, “I’m proud of you, son, and I support you” — it made me realize that my dad isn’t who I thought he was when I was younger. I thought he just was there to put me down and degrade me and think the worst of me all the time. And that wasn’t the case.

He just was a hurt person at the time. He had a lot to figure out during American Idol. My dad didn’t have a lot of close friends that he could talk to. His family was falling apart. My mom had left right before American Idol; she only came back because the kids needed someone to be there at the home [while I was in Los Angeles doing the show]. But my mom had wanted out of the marriage for a while. My dad’s best friend died while I was on American Idol, too, and that tore him up. And I think it just made him dive even more into getting lost in the world of David.

Your father didn’t always do things right, but as I said, he did put you on Idol, which changed your life in so many ways. In fact, the first LGBTQ+ person you ever discussed homosexuality with was one of your fellow Idol contestants. She’s now known as Adore Delano, who found much greater fame on RuPaul’s Drag Race, and has since transitioned. But as you clarify in your book, you spoke with her and she gave you permission to refer to her in context as Danny Noriega, which was her name when she competed on American Idol Season 7. And Danny was very out, very opposite of the childhood you’d had. I think for a lot of kids watching at home, seeing someone like Danny Noriega make the top 16 on a mainstream TV show was a big deal. And meeting her made a big impression on you as well.

Yeah. I was very devout, focused on my beliefs, Mormon at the time. And Danny was a year older than me. And so, with Adore, I saw her life and I thought, “That’s wrong.” And yet at the time I was like, “I feel so seen and safe with this person. I don’t even understand why.” I didn’t understand that I could relate to an extent of what her experience was, to an extent of being misunderstood for your sexuality or your identity. We both could relate to each other, but I felt like I could somewhat pass and blend in. Danny couldn’t. Adore couldn’t. Adore was a lot more flamboyant naturally than I was. She couldn’t hide. She just had to be herself. She had to get bullied. She had to get the brunt of it. She had to get called all kinds of names to her face all the time. And she learned how to be tough and to fight. In school, she would get in a lot of fights because of it, but it’s because she was just like, “I’m not going to let other people tell me what I am. I’m not going to let them decide whether I am worthy of being here or not.”

I admired that so much, because I was letting everyone decide for me. I was hiding. I was doing everything I could to be what I wasn’t. And I didn’t understand the scope of that; I didn’t understand it at the time and who I was. I was in very much denial, which is why I didn’t understand why I related to Adore. I just knew I could let my guard down with her. And yeah, I’m so grateful. She didn’t pressure me. She didn’t try to push me. I think sometimes people feel like, “A-ha! I knew [that David Archuleta was queer]!” And it’s like, OK, cool. I didn’t. I needed my time to figure that out.

I’m so glad you did.

Thank you!

On that American Idol season, George Michael performed on the finale. By then he was out, and now he’s considered an LGBTQ+ pioneer. But he had been outed in a way that at the time was considered disgraceful and scandalous. Do you have any memories of George that day? Did he make an impression on you?

Unfortunately, George didn’t allow any of us to be on the stage, and he didn’t even want us on the stage with him when we were singing his songs. He wanted everyone off the stage by the time he was there. He did not want to interact with any of us; I don’t know why. So, I didn’t really think anything of him [back then]. I didn’t really know his music and I didn’t really appreciate him. I didn’t think too much else of it because I was just like, “OK, this guy doesn’t want to even interact with us on our show.” It wasn’t until I came out that I really became a fan of George Michael and appreciated his music, his message, his journey, what he had to go through with the public scrutiny. At a time when it wasn’t yet accepted, he was bold to be himself. I went back and listened to his music and I was just like, “Oh, this makes so much sense now.” It spoke to me, and it was the motivation I needed. I played “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me” on repeat, as well as “The Voice Within” by Christina Aguilera, the day I came out. They just became my anthems.

Well, what George Michael’s music did for you when you were beginning your coming-out journey, maybe your music can do that for someone now. I think your story is going to help a lot of people.

Thank you. I hope so. I hope it’s encouraging for somebody out there. That’s the whole goal.

This Q&A has been edited for brevity and clarity.