Fifty years ago, Columbia Pictures and Raybert Productions released a fascinating ’60s celluloid artifact promised to be “the most extraordinary adventure western comedy love story mystery drama musical documentary satire ever filmed.” That film, Head, effectively (if temporarily) detonated the careers of reluctant TV teen idols the Monkees — but it simultaneously ushered in the New Hollywood and kickstarted the career of a certain future Oscar-winning actor.

“That was a very strange experience,” chuckled the Monkees’ Micky Dolenz, visiting Yahoo Entertainment in 2016 to discuss the Monkees’ comeback album Good Times!, when asked about the notorious cult classic. “[The Monkees series co-creator and Raybert co-founder] Bob Rafelson brought this guy in one day. He was a B-movie actor, and he said, ‘It’s a friend of mine, and he wants to do some writing. And his name is Jack Nicholson. … Jack’s going to hang around the set and go to your homes and hang out with you at home and you’re going to just see what kind of movie we put together.’”

The strategy came at a point in the made-for-TV band’s career where they were feeling stifled onscreen (NBC forbade them from making overt political statements or even saying the word “hell” on the “Devil and Peter Tork” episode). The Monkees had also seized creative control of their musical output with their third album, Headquarters, the year before. So, while Dolenz and his bandmates Michael Nesmith, Peter Tork, and Davy Jones (credited as “David Jones” in Head) didn’t quite know what to expect when they joined Rafelson and Nicholson for a weekend brainstorming trip to Ojai, Calif., they did all agree that Head would not be a typical pop-music matinee.

“When the idea of doing a movie had come up, the obvious way to go, which would have been much more commercial, would have been to do a 90-minute version of a Monkees episode,” Dolenz told Yahoo. “And it was discussed. And I remember agreeing with [Rafelson, who argued], ‘I don’t know if we should do that. We’ve been under the thumb of the censors and of the network. This gives us an opportunity to go out and push the envelope a little bit, in humor and in the sensibility of the whole thing.’”

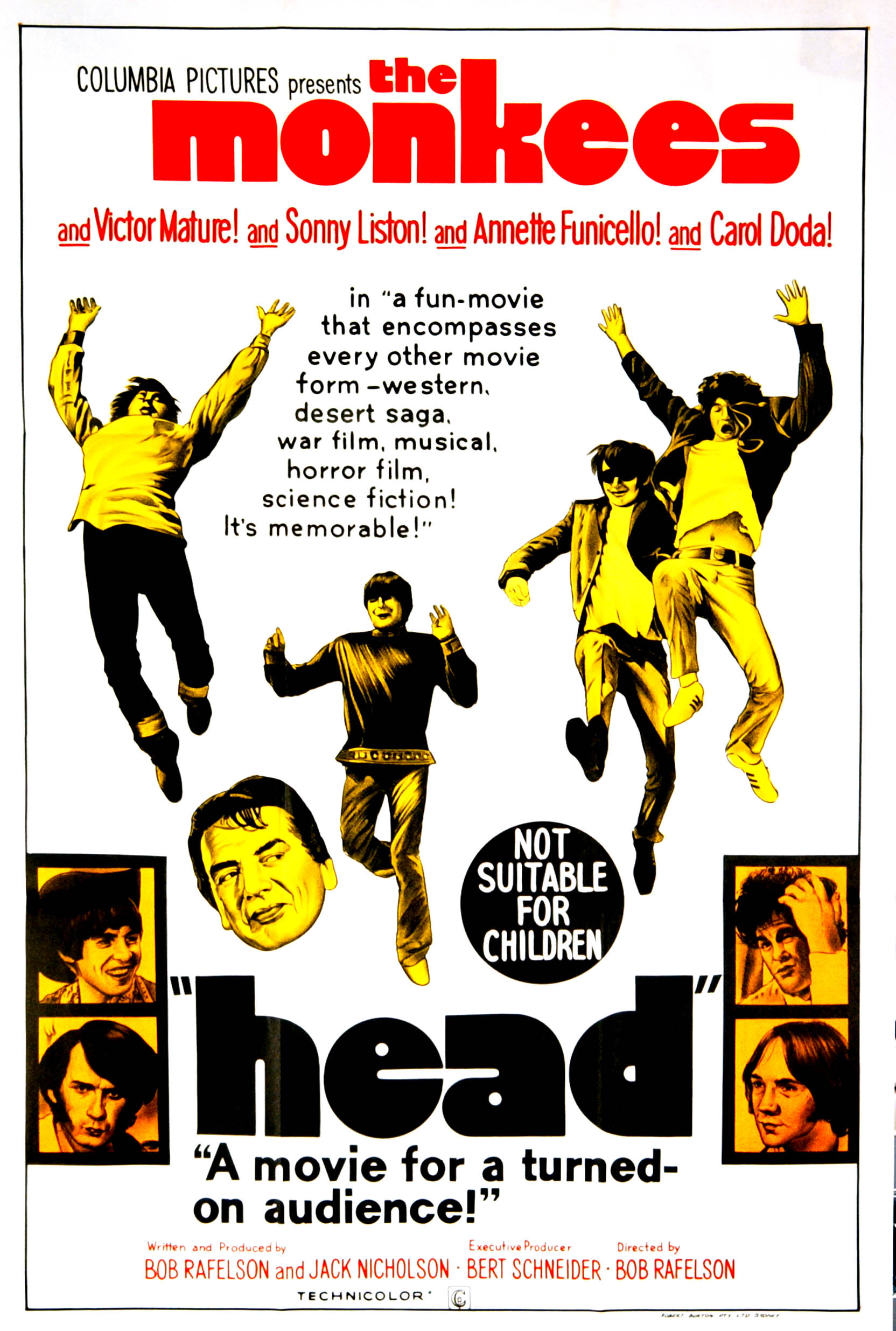

Poster courtesy of GAB Archive/Redferns

Nicholson used tape recordings of the Ojai sessions to write the screenplay for Head, reportedly — and not surprisingly, given the bizarre result — while dropping acid. (Nicholson had written the script for Roger Corman’s countercultural LSD film The Trip the year before.) Suffice to say, the super-meta movie — filmed around Southern California one month after the cancelation of the band’s Emmy-winning TV series, directed by Rafelson and produced by Rafelson and his Raybert partner and Monkees co-creator Bert Schneider — definitely would not have made it past those NBC censors.

Head plays out like a lysergic dream sequence — beginning with Dolenz leaping off Long Beach’s Gerald Desmond Bridge, then frolicking with a school of hippie mermaids in the kaleidoscopic waters below to Carole King and Gerry Goffin’s woozy, psychedelic epic “Porpoise Song” (which is now widely regarded as one of the all-time greatest Monkees tunes).

Over the course of the ensuing “circular” 86 minutes (the film was deliberately crafted to have neither a beginning nor an end, so that viewers could drop in at any point in the disjointed storyline), the following events transpire: The Monkees find themselves trapped in a giant vacuum cleaner (with a baseball-bat-sized blunt). The band members engage in a kissing contest with a nubile brunette (spoiler alert, it ends in a four-way tie). They’re terrorized by both a King Kong-sized Victor Mature and an enormous bloodshot eyeball that dwells inside a public restroom’s medicine cabinet. And so on.

“We hope you like our story/Although there isn’t one,” declares the film’s Nicholson-penned song “Ditty Diego — War Chant,” a vicious parody of the Monkees TV show’s original cheery theme song. But amid all the drug-addled chaos and kookiness and non sequiturs and laughably cheap green-screen, Head does offer many compelling, fourth-wall-shattering moments, bravely skewering the Monkees’ goody-goody image and the entertainment industry in general.

In “Ditty Diego,” the band members address their prefab personas and lack of credibility, intoning, “Hey, hey, we are the Monkees/You know we love to please/A manufactured image/With no philosophies.” They address crass consumerism via Dolenz’s losing battle with an exploding Coca-Cola vending machine and the band members’ portrayal of jumbo dandruff flakes in an obnoxious shampoo commercial. Tork gets into an onscreen argument with Head’s directors over one violent movie scene’s direction, arguing that it will alienate the band’s teenybopper fanbase. Jones, the main heartthrob of the group, dumps fellow teen idol Annette Funicello (who plays his small-town girlfriend), then competes in a boxing match with a man twice his size and allows his pinup-pretty face to be pounded into pulp.

And, after Jones does a delightful, old-fashioned soft-shoe routine with choreographer Toni Basil to Harry Nilsson’s “Daddy’s Song,” he encounters Frank Zappa, who, in the movie’s most amusingly deadpan one-liner, tells him, “That song was pretty white.”

Far less amusing, but just as effective, is the juxtaposition of footage of screaming female Monkees fans alongside images of the Vietnam War (including the execution of Viet Cong operative Nguyen Van Lem), and a scene in which the Monkees, after performing Nesmith’s “Circle Sky” at a cult-like concert, have their mannequin doppelgängers torn apart by those same hysterical fans.

“Who knows what it’s really about. But I can give you a couple of hints,” Dolenz told Yahoo Entertainment. “What I think it was about, on sort of a philosophical level, is breaking out of the Hollywood mold. … There’s one scene in the movie which I think speaks to that, and it’s the kind of spine of it. It’s the one where Mike and I are cavalry guys, and we’re being attacked by Indians in covered wagons. Teri Garr — in her first onscreen [speaking] appearance — is wounded, sitting there, dying. And I’m there with my rifle and Mike’s looking out for the Indians, and all of a sudden the special effects guy … hits me with three arrows. And I look down and I go, ‘Oh, Bob’ — and I’m talking to Bob Rafelson, the director — ‘That’s it! I’m finished! I’m through with all this fake Hollywood!’ And I break off the arrows, throw down the gun, turn around, and walk right through the back of the set, through the big painting, the scrim. Tear a big hole in it and walk out.”

Most people didn’t understand or appreciate what Head was trying to accomplish, and negative audience response at an August 1968 test screening led the film’s creators to trim 24 minutes from its original length. But when the finished Head officially premiered three months later, on Nov. 6 in New York, it still flopped, eventually recouping only $16,111 of its $750,000 production budget. (Perhaps it was a bad omen that Nicholson and Rafelson were arrested at the premiere, after Nicholson tried to affix a Head sticker on a police officer’s helmet.)

“It did get some critical acclaim, but it didn’t sell any tickets, because nobody got it,” Dolenz shrugged. “The kids didn’t get it at all; they were expecting a Monkees episode. I think it was even rated where little young kids, our youngest fans, couldn’t even get in, because there was some violent things; I can’t remember what the rating was.” [Editor’s note: Some posters advertised Head as being “not suitable for children,” although in the U.S. it was surprisingly rated G.]

Despite Head’s initial failure, and the fact that the Monkees split up shortly thereafter, the movie changed Hollywood in unexpected and lasting ways. “There was no independent film industry [back then]. … The studios controlled everything,” Dolenz explained. But just one year later, in 1969, provocateurs Rafelson and Schneider released the groundbreaking Easy Rider, directed by Dennis Hopper (who had a cameo in Head) and starring Nicholson and The Trip’s Peter Fonda. A year after that, Rafelson and Schneider formed BBS Productions with Stephen Blauner and released the Rafelson-directed Five Easy Pieces, which was nominated for four Oscars (including Nicholson for Best Actor). And it all started with the Monkees.

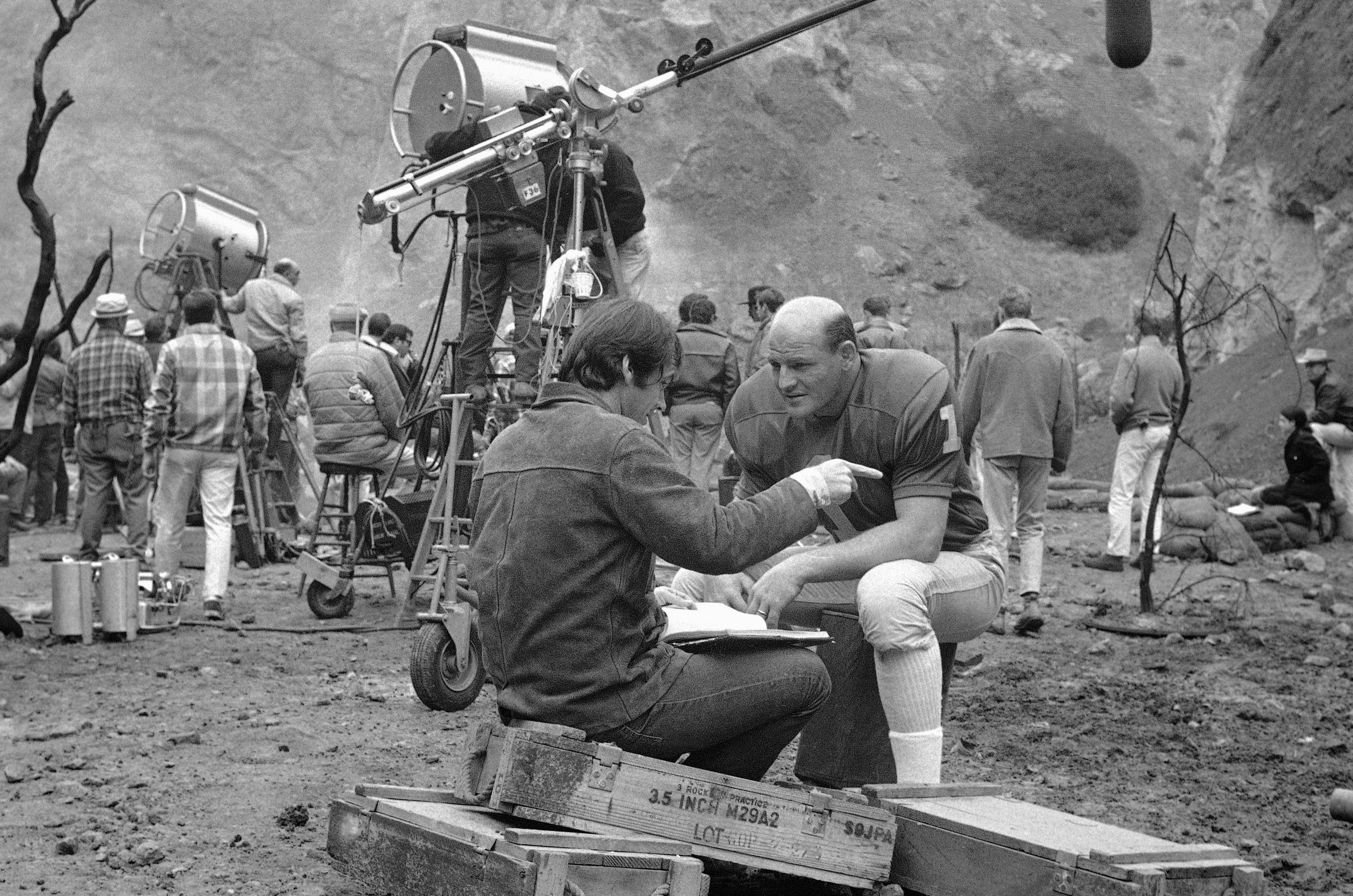

Football player Ray Nitschke, making his acting debut, with Jack Nicholson on the set of ‘Head.’ (Photo: AP/Harold Filan)

“I would argue Head had incredible influence on Hollywood over the next several decades,” musician Sean Randall wrote in Huffington Post in 2017. “The awkward, disjointed, deep thought randomness and repeated themes reminded me strongly of David Lynch and Mulholland Drive. … The film also [has] a slightly less comedic And Now for Something Completely Different vibe, one of Monty Python’s cinematic efforts after Head came out. … Further, I’d wager that this film, while not being successful itself, opened the door for other musician cinematic vanity projects, like Pink Floyd’s The Wall. Or the lesser-known Metallica 3D concert film Through the Never, which definitely looked to Head for inspiration.”

“Now [Head has] become a real cult thing,” Dolenz proudly said of the film, which was released on Blue-ray in 2010 and whose soundtrack, featuring additional musical contributions from Ry Cooder, Neil Young, Stephen Stills, Leon Russell, and Jack Nitzsche, is now a coveted collector’s item. “I know Quentin Tarantino, when I first met him, he said it’s like top five for him. Edgar Wright and a lot of people have said that. It’s like top five movies for those kind of filmmakers.”

This article originally ran on Yahoo Music.